STOP THE HYSTERIA: China’s CBDC does not have surveillance “superpowers”

What if I told you that it provides better privacy than your credit cards? Read on!

Not a day goes by when I don’t read that China’s new central bank digital currency (CBDC) is a dystopian nightmare and a blow to privacy in China. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth, and if we break it down, we can see how China’s digital yuan or e-CNY will be privacy positive for Chinese citizens.

Some may be surprised to find that the digital yuan does not provide a direct line to the police with every payment! What if I told you it was better than western credit cards? Read on.

What may surprise many is that the digital yuan provides a greater degree of anonymity when making purchases than the payment platforms Alipay and WeChat Pay that most of the nation is using now. And how about this, digital yuan provides greater anonymity than the credit cards you use now in the West.

For some, this may come as a shock as they assume that the new e-CNY has a direct line to the police with every payment you make spied upon by the government. However, the reality is very different because of the design of China’s e-CNY and the recent passage of some of the world’s most strict privacy laws.

Anonymity by design

To better understand what data you hand over when you make a payment with the digital yuan, we first need to take a look at how the digital yuan is designed. For example, many assume that your name and purchase amount are attached to every transaction when you use the digital yuan. That may be how it works with credit cards but not what happens with the digital yuan.

The digital yuan is built using much of the same technology used in bitcoin and cryptocurrencies. Unlike credit cards with your name on the front, encrypted e-CNY, “coins” or “tokens” do not contain a digital version of the user’s name. Instead, they have the numerical address of your digital wallet, which does not attribute ownership to a person. This means that a digital yuan spent at a coffee shop is disconnected from the actual name of the person who spent it. That data is simply not available to the coffee shop or anyone else. Your name and what bankers call “know your customer” (KYC) data that would allow the wallet address to be connected to the user is held separately and not available in all transactions.

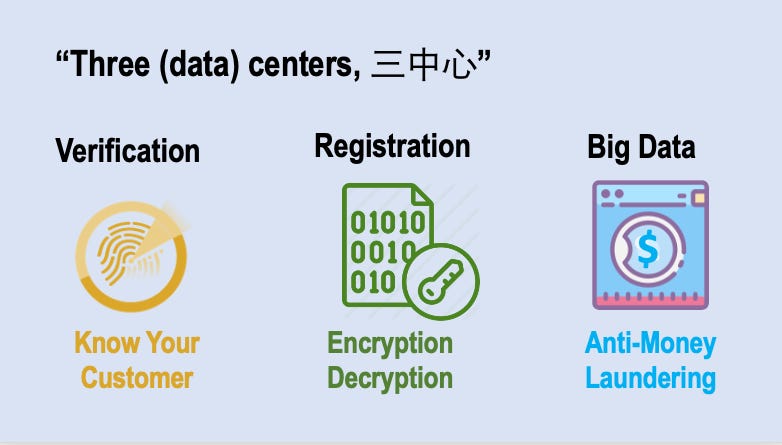

The digital yuan is designed around three distinctively different data centers, each with a separate role in processing digital yuan transactions. The data centers are Registration, where the KYC data is kept; Verification, which decrypts digital yuan coins to prove they are valid; and a Big Data center which analyzes digital yuan usage to avoid fraud and misuse. The division of data into these three different data centers is critical to the operation of the e-CNY and CBDCs in general. Storing names and KYC data separate from the transactions ensures that government does not have unlimited real name tracking of CBDC users.

The know your customer and big data are almost identical to the systems run by banks. Unlike your bank with e-CNY the systems are separated. The registration center is the engine for the system in that it supplies the computers required to encrypt and decrypt (hash) digital yuan coins to validate them.

The critical thing to understand is that when the PBOC receives a transaction, it goes to the Verification and Big Data centers for processing and analysis. All through this process, no one knows who spent the coin. The only way the coin can be attached to the spender’s real name is by accessing the Registration center, which is segregated and off-limits. The only way for police or tax authorities to get access is through a judge who will issue a warrant to connect the spender's name with the transactions.

Ironically, this is precisely the same process with credit cards in the US and EU. If the tax or police want credit card information, they have to go to a judge and show why they need this data before the credit card company gives it to them. While the technology behind credit cards and e-CNY is different, the process for “unmasking” a user is the same.

The process for connecting an e-CNY user with their spent money requires a legal warrant just as it does in the US or EU.

Now here’s something that may surprise you. When you go to a coffee shop and buy a coffee with your credit card, the coffee shop knows who bought the coffee. So you have no presumption that the transaction is private, just like Alipay and WeChat Pay users. Moreover, your real name data is left behind when you buy a coffee with any of these systems, unlike the new e-CNY. So it is demonstrably true that people paying with digital yuan have greater anonymity than those using the payment platforms in China or credit cards in the West.

Anonymity, however, does have limits. The People’s Bank of China recognizes the right to complete anonymity with small purchases where many users would traditionally use cash. This means that these payments are not subject to being connected to a user with KYC data. Larger purchases are not anonymous as they need to be subject to money laundering and other financial crime controls. E-CNY users have complete anonymity overall purchases up to RMB 2000 or roughly US$300. Beyond this amount, e-CNY purchases can be reconnected through a warrant and connection of KYC and payment data.

Still, wouldn’t it be nice if your credit card was anonymous for up to US$ 300? Most people find it surprising that the e-CNY has greater levels of anonymity than the cards they use every day.

Data protection laws

Many astute readers may be thinking that as all of these transactions are occurring on your phone, there is a loophole where telephone data may be used to track payments. However, two things prevent this from happening.

First, any digital yuan stored on or transmitted by your phone is cryptographically coded so that no one can read it. The digital yuan requires the services of the “verification” center, which is equipped with specialty decryption algorithms to decode these coins, which, even if decoded, would not reveal your identity.

The second critical feature is China’s Personal Data Protection Law. In August of 2021, the Chinese government passed a new “Personal Information Protection Law” (PIPL), which mandates that all personal digital data be protected, including phone data. These laws are similar to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or the California Consumer Privacy Act and put severe restrictions on what mobile phone companies can do with your data. In fact, they are so strict that they largely prohibit the sale of even anonymized data in recognition that it may be “deanonymized” through the use of big data.

According to Mu Changchun, Director General of China Digital Currency Research Institute: “Under that law, the telecom companies cannot release any information, identity information, to any third parties, including the central bank.”

China’s new PIPL laws are tough and the US does not have anything that can compare. China’s new PIPL and algorithm laws that control AI are ground breaking and being studied in the EU and US.

It’s hard to square comments that the digital yuan is “spyware” when the critical identification data is simply inaccessible to government officials without a warrant. Critics will, of course, say that they don’t trust China to honor these rules. These are, however, precisely this kind of detail-driven bureaucratic rules that China excels at enforcing. The larger issue of trust in government whether in China or the West is a far larger issue than I can possibly cover.

e-CNY does not have superpowers

Many talking about the digital yuan or CBDCs in the West seem to believe that they have surveillance “superpowers.” Of course, the government will use these new surveillance superpowers against citizens in China or the West, and we should all live in terror. For most Chinese citizens, their payments are already digital, as the majority of the country has already gone “cashless.” This is also true to a lesser extent in the US or EU, where most can say that most of their payments are made on our devices or cards.

The reality is that whether it's Alipay, WeChat Pay, Visa, Mastercard, or e-CNY, all of our digital transactions leave a digital footprint that government can follow, provided they have a warrant. Those who say that the e-CNY’s tracks are easier to trace or somehow imbued with superpowers don’t understand China’s payment networks or those in the West.

In the case of Alipay and WeChat pay, both systems use a government-operated credit card payment network called UnionPay, so most payments in the nation are already carried on government systems. This makes the transition to e-CNY, a new government-sponsored payment system, anti-climactic for most Chinese.

What’s your superpower? Despite what you’ve been told, the e-CNY does not have surveillance superpowers!

For electronic payments in the West, we primarily use credit card networks that are privately run but whose payment data is an open book to our governments when a warrant is provided. And that’s the irony of the discussion surrounding CBDCs. In reality, CBDCs does not give the government “new” surveillance powers, whether in China or the West. If the government gets a warrant, it is allowed to look into all of our digital life and whether you use a CBDC or not is irrelevant.

The irony is that many in the West claim that the e-CNY is being developed solely for surveillance. Their lack of knowledge of China’s payment systems is evident whenever they say this. In 2019 Yao Qian, the former leader of China’s digital currency research, commented that there was no need for the PBOC to build a CBDC to monitor payments because that technology already exists. Saying: “In fact, third-party payment technology can already enable the transparency of all real-time transactions.” This is indisputably true for WeChat Pay and Alipay, just as it is for Visa and Mastercard or any payment system using cards in the West.

Some may say that the Chinese government’s access to transaction data through the “Big Data” center is at the root of surveillance even if it is not tied directly to names. Here too it’s hard to make the case that this surveillance is much different than that of anti-money laundering surveillance conducted by credit cards in the West, or by EU and US governments purchasing credit card data to monitor the economy. In both cases, transaction data is subjected to analysis that is analogous to China’s. I consent that e-CNY data will be more up-to-date, but the level of granularity will be identical to that available from card companies in the West that commonly sell data with identifiers for individual cards.

Corporate Surveillance

So far, we’ve discussed how privacy from government surveillance is built into the e-CNY both by design and through privacy laws. However, this still leaves one critical area, corporate surveillance by the payment platforms in China or credit card companies in the West.

Most of us know all too well the experience of buying something online only to receive email or text messages over the following days or weeks asking us to buy related products. The recommendations, of course, come from surveillance of our purchasing behavior through digital e-commerce and payment platforms.

In China, both payment platforms are famed for their ability to collect personal data used for extending credit or resold for advertising and marketing purposes. Unfortunately, this practice isn’t limited to China. While our Western credit card companies may say that our data is “anonymized,” they collect and sell so much data about us that much of our payment life is an open door.

Further privacy erosion occurs when big data equipped advertising and marketing companies purchase data from data brokers to deanonymize credit card data. This isn’t new, and the amount of data collected by big tech, including our payment data, is an ongoing issue in China and the West.

Credit card data is “gold” in the hands of the card companies who sell it off to data brokers. When combined with other data sets like cell phone location it’s not hard to “deanonymize” card data.

This is where the e-CNY excels because it leaves no data behind with vendors when making payments. In addition, there is no payment intermediary like WeChat or Visa collecting data on the transaction. For private payment companies, data is a revenue stream. For the PBOC, selling data is unthinkable.

The PBOC’s White Paper on the digital yuan made the case quite clearly: “The e-CNY system collects less transaction information than traditional electronic payment and does not provide information to third parties or other government agencies unless stipulated otherwise in laws and regulations.” But, sadly, few of those proclaiming e-CNY’s nightmarish privacy standards seemed to pay much attention.

Stop the hysteria.

China’s digital yuan will increase privacy for China’s digital payment users compared with the corporate-run payment platforms they currently use. While the platforms have done a great job in helping China go cashless and won’t go out of business, the e-CNY will give people a privacy-protective alternative to the data-hungry payment platforms. In addition, introducing another means of payment that allows for the disintermediation of third parties from the payment process is a significant benefit unique to the e-CNY.

Payment anonymity up to a limit of RMB 2000 $300 is a real benefit not just in China, but also in the West, where there is no equivalent technology. Yet still, pundits rail against the digital yuan when their coffee purchased with a Visa card is subject to corporate surveillance and data monetization on levels that China’s e-CNY system could never achieve.

E-CNY does not have surveillance superpowers, and pundits who make it out to be solely an instrument of state surveillance seem to almost universally ignore the ability of the state to use credit cards or payment platforms for similar means. This oversight is intellectually dishonest and misrepresents the current state of digital payments in China and the West. The technology behind e-CNY does not imbue the state or the e-CNY with surveillance superpowers.

Thanks so much for reading!

More of my writing, podcasts, and media appearances here on RichTurrin.com

Contact me https://richturrin.com/contact/

Rich Turrin is the international best-selling author of "Cashless - China's Digital Currency Revolution" and "Innovation Lab Excellence." He is an Onalytica Top 100 Fintech Influencer and an award-winning executive previously heading fintech teams at IBM following a twenty-year career in investment banking. Living in Shanghai for the last decade, Rich experienced China going cashless first-hand. Rich is an independent consultant whose views on China's astounding fintech developments are widely sought by international media and private clients.

Please check out my best sellers on Amazon:

The best and only way to stop such HYSTERIA:

1) provide the architecture of the complete solution of digital yuan (several views, of course)

2) provide an objective proof that the declared architecture (see item 1) does correspond the implemented architecture

3) guarantee that Digital Yuan will not be used outside the country soil, because, otherwise, it may be weaponized

Hope this will help. Good luck.